An Easy-to-prepare Mini-scaffold for Dna Origami

Abstract

Biological materials are self-assembled with near-atomic precision in living cells, whereas synthetic 3D structures generally lack such precision and controllability. Recently, DNA nanotechnology, especially DNA origami technology, has been useful in the bottom-up fabrication of well-defined nanostructures ranging from tens of nanometres to sub-micrometres. In this Primer, we summarize the methodologies of DNA origami technology, including origami design, synthesis, functionalization and characterization. We highlight applications of origami structures in nanofabrication, nanophotonics and nanoelectronics, catalysis, computation, molecular machines, bioimaging, drug delivery and biophysics. We identify challenges for the field, including size limits, stability issues and the scale of production, and discuss their possible solutions. We further provide an outlook on next-generation DNA origami techniques that will allow in vivo synthesis and multiscale manufacturing.

Introduction

Biological materials of living cells are synthesized in a bottom-up manner. The information encoded in biomolecules is exploited to guide their own self-assembly and the hierarchical formation of larger complexes, keeping near-atomic precision along sizes spanning from nanometres to the macroscopic scale. By contrast, in vitro manufacturing of complex 3D structures down to the nanometre scale has usually lacked such precision and controllability. In the 1980s, Seeman first proposed the rational design of an immobile Holliday junction1, which turned DNA into a nanoscale polymer extending in two dimensions instead of simple 1D double helices. This work signalled the debut of DNA nanotechnology, which allows massively parallel synthesis of well-defined nanostructures, with synthesis on a picomole-scale generating 1012 copies of a product. Since then, various DNA nanostructures including double-crossover2, triple-crossover3, 4 × 4 (ref.4) and three-point star structures5 have been assembled using the junction of multiple short single-stranded DNAs (ssDNAs). These DNA tiles can be further assembled into periodic superstructures including nanotubes, 2D lattices and 3D structures including polyhedra, hydrogels and crystals6.

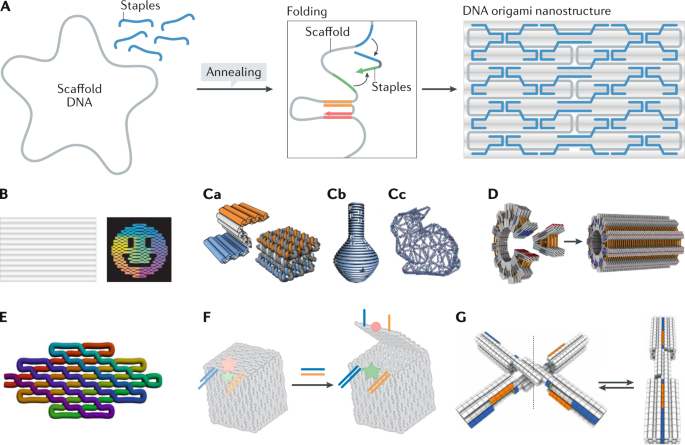

DNA origami technology, as a promising branch of DNA nanotechnology, is an effective technique for bottom-up fabrication of well-defined nanostructures ranging from tens of nanometres to sub-micrometres. DNA origami involves the folding of DNA to create 2D and 3D objects at the nanoscale. The concept of DNA origami relies on folding a long ssDNA called the scaffold (typically viral DNA ~7,000 nucleotides long), with hundreds of designed short ssDNAs called staples. Each staple has multiple binding domains that bind and bring together otherwise distant regions of the scaffold via crossover base pairing, folding the scaffold in a manner analogous to knitting7 (Fig. 1A). The geometries of the resulting structures can be programmed with the staple sequences. This programmability enables computer-aided design and universal synthesis protocols8,9,10 that make DNA origami an easy to use technology amenable to automated fabrication. Compared with tile-based DNA assembly strategies, DNA origami synthesis generally exhibits higher yield, robustness and the ability to build complex non-periodic shapes, which partially arises from the high cooperativity of multiple scaffold–staple interactions during origami folding11,12. Since the original demonstration of 2D patterns7 (Fig. 1B), virtually any arbitrary shape can be synthesized, from 1D to 3D structures with user-defined asymmetry13,14,15, cavities16,17 or curvatures18,19 (Fig. 1C). More recent progress includes hierarchical assembly of supramolecular structures20,21,22 (Fig. 1D), single-stranded origami23,24 (Fig. 1E) and dynamic structures6,25,26 (Box 1; Fig. 1F).

A | Principle of classic DNA origami. A long single-stranded scaffold DNA is annealed with multiple short staples (blue). The staples can bring together distant regions of the scaffold via base pairing (pairing sequences are marked red, orange, green and blue, for example), resulting in a prescribed shape. B | Representative 2D planar DNA origami shapes7. C | 3D nanostructures depicting a honeycomb lattice17 (part C a), a structure with complex curvature19 (part C b) and a wireframe structure with arbitrary shape15 (part C c). D | Superstructures hierarchically assembled from multiple DNA origami structures20. E | Single-stranded DNA/RNA origami23. The rainbow gradient represents the folding route starting from the 5′ and 3′ ends (red) to the middle of the strand (purple). F,G | Examples of dynamic DNA origami nanostructures: a DNA origami box89 whose lid is initially locked by two DNA duplexes and can be opened via strand displacement by oligonucleotide keys (blue and orange lines, lock and key strands; pink and green stars, fluorescent emission from Cy5 and Cy3 labelling; red circle, Cy5 lost emission) (part F); and a dynamic nanodevice26 switchable between two conformations (open and closed) upon the competition between base stacking (arising from the complement of blue and orange domains) and electrostatic repulsion, which is responsive to the change in temperature and/or Mg2+ concentration (part G). Part B adapted from ref.7, Springer Nature Limited. Part Ca adapted from ref.17, Springer Nature Limited. Part Cb adapted with permission from ref.19, AAAS. Part Cc adapted from ref.15, Springer Nature Limited. Part D adapted from ref.20, Springer Nature Limited. Part E adapted from ref.23, AAAS. Part F adapted from ref.89, Springer Nature Limited. Part G adapted with permission from ref.26, AAAS.

Full size image

A typical planar DNA origami structure contains approximately 200 staples with unique sequences and positions, which can serve as uniquely addressable points in an area of 8,000–10,000 nm2 (ref.6). The global addressability with nanometre resolution allows the structures to serve as elaborate pegboards or frameworks; by prescribing functional moieties on staples, various types of material can be site-specifically placed at specified locations on a DNA origami structure6,27. These achievements have shown great promise in the fabrication of structures enhanced by metal, silica, lipid or polymer coatings28,29,30 and as nanosystems for nanophotonic and nanoelectronic devices31,32,33,34,35,36. Dynamic DNA origami structures can be rationally engineered on the basis of structurally reconfigurable modules (Fig. 1F) that use strand displacement reactions25,37, conformationally switchable domains and base stacking components26, enabling various applications such as target-responsive biosensing and bioimaging38, smart drug delivery39,40, biomolecular computing41 and nanodevices allowing external manipulation with light or other electromagnetic fields42,43,44.

In this Primer, we summarize the methodologies of DNA origami technology, including origami design, synthesis, functionalization and characterization (Experimentation and Results). We highlight applications of origami structures in nanofabrication, nanophotonics/nanoelectronics, catalysis, computation, molecular machines, bioimaging, drug delivery and biophysics (Applications). We provide caution for using DNA origami with high reproducibility and reliability (Reproducibility and data deposition). We identify challenges for the field, including size limits, stability issues and the scale of production, and discuss their possible solutions (Limitations and optimizations). Finally, we discuss next-generation DNA origami techniques that will allow in vivo synthesis and manufacturing of multiscale-ordered materials (Outlook).

Experimentation

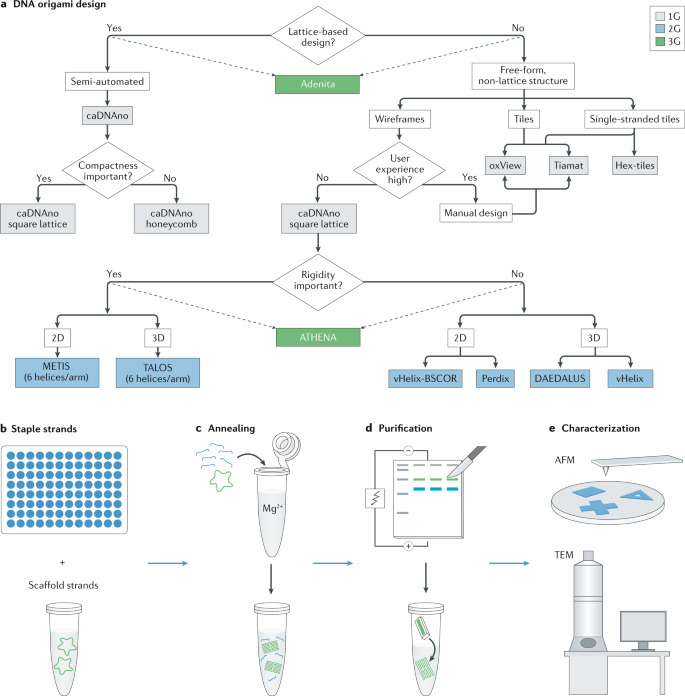

DNA origami objects with a rich diversity in dimension, geometry and shape have been produced, ranging from single layers to multilayers7,17 as well as from flexible wireframes to rigid polyhedra15,19,45. A typical experimental process for fabricating DNA origami is illustrated in Fig. 2.

a | DNA origami structures are usually designed using the software shown in the decision-making flow chart. The coloured boxes (grey, blue and green, design tools of the first (1G), second (2G) and third (3G) generation, respectively) represent the software that are best suitable for a given task. b | Staple strands are usually purchased commercially and stored in 96-well plates. Single-stranded viral DNA (usually from M13 bacteriophage) is typically used as a scaffold for DNA origami structures. c | The M13 scaffold mixed with staple strands (with a large excess) is assembled through thermal annealing in a saline buffer solution (typically with 12.5 mM Mg2+). d | The structures are usually purified using agarose gel electrophoresis, with the excision of DNA bands from the gel and purification of the structure. e | Characterization is mainly done using atomic force microscopy (AFM), which observes 2D and single-layer origami structures, or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to characterize 3D origami structures and multilayer structures.

Full size image

Design

The basic principle of DNA origami design is to translate the desired final shape into the folding route of a given scaffold and generate corresponding staple sequences that can fulfil the folding. Table 1 presents a comparative summary of the different software developed for designing DNA origami structures. The first-generation (1G) DNA origami design tools (for example, caDNAno8) were developed for designing various 2D and 3D origami structures. Detailed insights into designing origami by 1G software have been covered extensively elsewhere46 and can also be found in the references cited in Table 1. caDNAno remains the most mature and routinely used software for designing DNA origami8 (Fig. 2a). Other software such as Tiamat, SARSE-DNA, Nanoengineer-1, Hex-tiles, GIDEON, K-router and so on have also been used for DNA origami designs. These 1G design software require manual scaffold routing, and manual — or semi-automated, in the case of caDNAno — scaffold and staple crossover creation, requiring extensive expertise on this structure type and more technical knowledge for design of DNA origami.

Full size table

Second-generation (2G) design software have been developed to be more user-friendly and demand less technical knowledge than their 1G counterparts. The main advantage of using 2G software is the ability to generate staple sequences in an automated fashion from user-provided 3D designs. vHelix15 is the most widely used software in this category and also contains an integrated simulation platform that can predict the folding of the designed structures in standard DNA origami folding buffers. Other software such as DAEDALUS47 and TALOS9 for 3D origami and vHelix-BSCOR48, PERDIX49 and METIS10 for 2D origami are also available. Other automated design tools such as MagicDNA50 have been reported in preprints.

Recently, two new software have been reported that enhance the capabilities of DNA origami design by combining features from the 1G and 2G software. ATHENA51 integrates features of other existing 2G software, specifically that of DAEDALUS, PERDIX, TALOS and METIS. Adenita52 is an open source platform that combines almost all of the 1G and 2G design software capabilities. It can design lattice-based wireframes, multilayered structures, free-form tiles and single-stranded tiles. Adenita also contains an integrated simulation platform to predict the stability of the designed structures in buffer after their formation. ATHENA and, especially, Adenita are currently the most versatile design software available and they offer unprecedented user-friendly interfaces. Being integrated with the commercial nanoscale simulation software SAMSON, Adenita is the only software that also accommodates other biomolecules such as protein, lipid or drug molecules. This is expected to improve origami manufacturing feasibility as well as versatility of design for experts and non-experts alike. We therefore label Adenita and ATHENA as third-generation (3G) design software. One considerable drawback of 2G and 3G software is that they are more recent and less widely tested across different laboratories. Figure 2 presents a decision-making flowchart to choose the right design software for designing DNA origami.

Screening many different origami designs thoroughly through experimental work can be challenging. It is therefore important to predict the folding of designed origami computationally. All-atom molecular dynamics simulation has been successfully used for characterizing the structural, mechanical and ionic conductive properties of DNA origami in microscopic detail at the DNA single base pair level53,54. However, owing to the substantial sizes of DNA origami structures and the microsecond to millisecond timescales of complex events such as hybridization and dehybridization, it is computationally too expensive to use conventional all-atom molecular dynamics simulation packages such as AMBER55, NAMD56,57 and GROMACS58 for DNA origami structure predictions. Web server-based coarse-graining packages such as CanDo56 and COSM59 offer prediction of mechanical strain in designed origami structures that help minimize undesired folding in the assembly. A more comprehensive web server-based package, oxDNA60,61,62 offers the most versatile and practical approach in terms of ease of usage and features. oxDNA.org is as an entirely web-based application that uses rigid-body simulation to predict more advanced structural features such as the root mean square fluctuation structure, average hydrogen-bond occupancy, distance between user-specified nucleotides and angle between each duplex in the nanostructure. oxView, the graphical user interface of oxDNA, also offers de novo design of DNA nanostructures that is particularly useful when manipulating previously published designs for specific applications based on oxDNA simulations. The recently reported MrDNA63, which can perform all-atom molecular dynamics simulation within 30 min, offers the highest resolution as well as the fastest speed compared with other simulation packages such as oxDNA. The bottleneck for using MrDNA, however, is the requirement for parallel computing such as a CUDA-enabled graphical processing unit in a supercomputing cluster to run simulations, which is resource-intensive and needs significant coding knowledge. The choice of appropriate simulation packages is often determined based on the target applications and availability of resources60,61,62,63.

Assembly

The choice of the scaffold to use for DNA origami is determined by the size and complexity of the desired structure. The most commonly used scaffold is the m13mp18 viral genome 7,249 nucleotides long isolated from the M13 phage. Other typical scaffolds include p7308, p7560 and p8064, also derived from M13, which provide alternative scaffold lengths and sequences. These scaffolds can be purchased from companies, such as New England Biolabs, Guild Biosciences, Tilibit Nanosystems, Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and so on, or custom-made using asymmetrical PCR64, using enzymatic single-strand digestion of PCR-amplified double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)65 or by purifying phage-derived single-stranded genomic DNA66,67. Custom scaffold sequences can provide better control of the overall size of the final object. However, scaffolds derived from phages require inclusion of multi-kilobase DNA sequences that cannot be altered or removed, constraining design possibilities. Breaking away from the M13 genome in terms of production of scaffolds with custom size (short and long) and sequence could provide more design possibilities and enhance development of the DNA origami method68. Clearly, the size of a single DNA origami structure is limited by the length of the scaffold used for folding. Efforts in scaling up the dimensions of origami units include the use of longer single-stranded scaffolds64,65,67 or the application of short scaffold-parity strands69. This strategy uses a set of randomly generated sequences typically 42 nucleotides long that are complementary to segments of staples extending from the origami shape and partially hybridized to the scaffold. In this way, additional helical layers can be bound to the scaffold-related origami structure, eventually enlarging its dimensions. After exporting the sequences of the designed staples from the software as .csv or .txt files, the staple strands are mainly purchased in the form of synthesized oligonucleotides in 96-well plates (from, for example, IDT or ThermoFisher Scientific).

Given that the stability of DNA base pairing is sensitive to cation concentration, the yield of DNA origami structures in terms of the fraction of correct structures is highly dependent on cation concentration. Most protocols for the assembly of DNA origami involve pH 8 Tris–acetate–EDTA (TAE) buffers with different concentrations (5–20 mM) of Mg2+ (MgCl2). The optimal concentration of Mg2+ varies with the complexity of the DNA origami structures. The most commonly used buffer contains 12.5 mM Mg2+. Higher concentrations (16.5–20 mM) are used for 3D structures, where higher base pairing stability is desired to maintain highly folded conformations, whereas lower concentrations (5–10 mM) are used for wireframe origami or tiles. In addition, many wireframe or closely packed origami structures can be folded with higher concentrations of other cations (such as Na+) instead of magnesium70,71. However, DNA origami structures synthesized in buffers with high Mg2+ concentrations may become structurally unstable when transferred into low-salt solutions72.

DNA origami structures are folded via one-pot self-assembly7,73,74. Table 2 presents the best practices for working with the reagents necessary to create DNA origami. In general, to reduce non-specific aggregates, the concentration of staple strands is 10–20× higher than the concentration of scaffold strands. For dynamic DNA structures, the staples involved in dynamic reconfiguration are often purified by denaturing PAGE to ensure 100% incorporation of these important staples into the desired location in the structure. The staple to scaffold ratio for these staples is generally set as 1.5–2 (ref.75) to preferentially promote intramolecular over intermolecular interactions and should be optimized depending on the desired dynamic function. The mixture undergoes a thermal annealing process, in which it is heated to near boiling for a short time and then gradually cooled to allow spontaneous self-assembly of DNA origami7,11,12,73. The specific annealing procedure depends on the complexity of the DNA origami — small wireframe structures and 2D origami need a few hours, whereas multilayer 3D structures may require several days because the high degree of folding is less thermodynamically favoured. In addition, stepwise assembly may be involved for creation of structures integrated with other functional materials, or hierarchical structures as discussed below74. The ability to fold complex DNA nanostructures with 100% yield at a constant temperature would be valuable76.

Full size table

Hierarchical assembly

The construction of hierarchical assemblies made of origami units (also called super-origami) was first proposed by Rothemund and mainly based on canonical DNA hybridization7. Subsequent work demonstrating sticky end-based assembly of DNA origami tiles into 2D lattices has expanded the capacity to generate bottom-up pattern complexity77, whereas lipid bilayer-assisted self-assembly has offered the possibility of fabricating supramolecular architectures in a micrometre space78,79. Recently, novel methods have emerged for the predictable self-organization of origami shapes, making those structures excellent components for ordered assemblies of micrometre dimensions20,21,26,74,80,81,82. DNA origami structures exploit stacking81, a kind of nucleobase interaction that takes advantage of the dense set of blunt ends at the edges of the structures. Such bases can establish base stacking interactions with exposed terminal bases at the boundaries of a different origami unit. The binding force between origami components can therefore be manipulated by the suitable choice of the number and base sequence of the edge–staples to promote geometric matching for maximal surface contact between facing edges. In other words, shape complementarity emerges as an additional factor for controlling the hierarchical assembly of DNA origami architectures20,26,80,81.

Purification

Purification and enrichment are crucial steps to use DNA origami structures for optical/electronic and biochemical/biomedical applications, especially when the structures require site-specific functionalization. The quality and purity of DNA origami structures can be assessed with agarose gel electrophoresis owing to the difference in gel migration rates17 between correct products and by-products. A detailed overview of the purification methods has been covered elsewhere46 and is beyond the scope of this Primer. Commonly used purification methods include gel purification83, ultrafiltration84, polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation85, ultracentrifugation86 and size-exclusion chromatography46. Depending on the application, the optimal purification method should be chosen by comparing quantitative (yield, duration) and qualitative (volume limitation, dilution, residuals, damage) measures73. For example, PEG precipitation promotes a high yield of the target species but also introduces residual PEG molecules; filter purification with molecular weight cut-off membranes provides residual-free separation but is limited in volume and may lead to non-specific aggregation in some cases; and gel purification is suitable for bandpass molecular weight separation, for example to separate modified DNA origami structures and the unbound moieties, but its yield is low and this method generally introduces agarose and ethidium bromide contaminants (Fig. 2d).

Results

In this section, we provide typical characterization data of DNA origami assemblies using ensemble and single-molecule techniques (Table 3). These techniques can inform users about the self-assembly process by providing information such as the yield and correct formation of the target structure, and the fraction of side products present, including high-molecular weight aggregates and misfolded and partially assembled intermediates.

Full size table

Ensemble characterization

The first piece of information needed on the self-assembly process is whether it succeeded and to what extent. To this end, the assembly mixture is analysed with ensemble methods such as gel electrophoresis, UV–visible and fluorescence spectroscopy, and circular dichroism. These techniques provide the average chemical or physical characteristics of the bulk of the molecules in solution, as they are able to discern between groups of molecules with similar properties but unable to pick out individual molecules. The outcome of the assembly reaction is examined in terms of populations of end products whose molecular details are unknown.

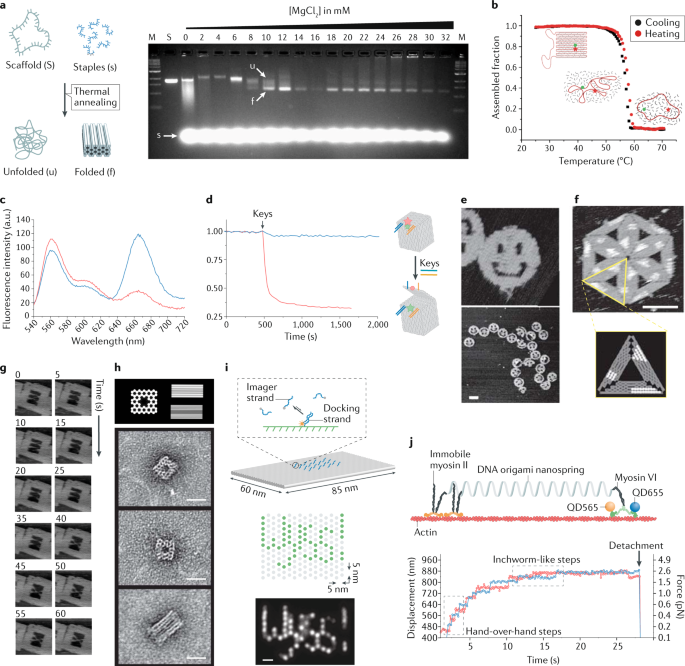

Gel electrophoresis is the method of choice to assess self-assembly performance17,69,70,76. Upon application of an electric field, DNA molecules migrate along a polymer gel matrix according to their size, charge and shape, enabling the separation of multimers of different orders as well as misfolded and/or partially assembled intermediates (Fig. 3a). DNA is then visualized by staining the gel with an intercalating UV-fluorescent dye, and products are quantified using fluorescence gel scanners and modern software tools. Alternatively, identification and isolation of the product of interest can be done using fluorescent dyes84. These are incorporated into the DNA nanostructure, substituting selected staple strands of the origami assembly mixture with their fluorescently modified analogues, commercially available in different forms at an affordable price. When combined, gel electrophoresis and fluorescent probes can be used to check the extent of staple incorporation and hybridization defects87. Besides their use as markers, photoactive compounds capable of Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) can be employed to monitor dynamic processes of structural reconfiguration in real time12,88,89,90,91,92 (Fig. 3b–d). Indeed, as the number and distance among the fluorophores in the final construct are fully predictable, any structural transformation that implies a change in their spatial configuration can be monitored and quantified by FRET spectroscopy, allowing, for example, insights into the thermodynamics of the self-assembly process or the kinetics of isothermal transformations26.

a | Agarose gel electrophoresis of the self-assembly products obtained at increasing magnesium ion concentrations (from 0 to 32 mM)70. b | Thermal-dependent Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurement of the assembly and disassembly of DNA origami microdomains (green and red dots indicate, respectively, a fluorescein and a TAMRA molecule)92. c | Ensemble FRET measurements of a closed DNA box before (blue curve) and after (red curve) the addition of keys89. d | Kinetics of lid opening monitored by the change in emission of the donor (red curve) upon addition of key oligonucleotides (black arrow) or an unrelated oligonucleotide (blue curve). Initial fluorescence was normalized to one. Schematic of the process indicated in the right panel89 (blue and orange lines, lock and key strands; pink and green stars, fluorescent emission from Cy5 and Cy3 labelling; red circle, Cy5 lost emission). e | First atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of quasi-planar DNA origami structures7. Scale bar is 100 nm. f | AFM imaging of hierarchical DNA assemblies decorated with bulky molecules at predictable positions (shown as white sections)7. Scale bar is 100 nm. g | Topological reconfiguration of G-quadruplex motifs imaged for 60 s at 5-s intervals using fast-scanning AFM101. Image size is 160 nm × 160 nm. h | First electron microscope characterization of a space-filled 3D DNA origami structure under different perspectives17. Scale bars are 20 nm. i | DNA-based point accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (DNA-PAINT) super-resolution imaging of a DNA origami structure106 relies on the transient binding between a dye-conjugated imager strand (blue) and a docking strand (at the centre of the structure). Schematics of a 'Wyss!' pattern on a DNA origami surface with 5-nm pixel size (each green dot indicates a docking strand) and resulting single-particle class average (n = 85)302. Scale bar is 10 nm. j | Coupled single-molecule force spectroscopy/optical measurements of the stepping behaviour of myosin VI when tethered to an optically trapped DNA origami nanospring115. Part a adapted from ref.70, CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0). Part b adapted with permission from ref.92, ACS. Parts c and d adapted from ref.89, Springer Nature Limited. Parts e and f adapted from ref.7, Springer Nature Limited. Part g adapted with permission from ref.101, ACS. Part h adapted from ref.17, Springer Nature Limited. Part i adapted from ref.302, Springer Nature Limited. Part j adapted from ref.115, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Full size image

Less commonly, UV–visible and circular dichroism spectroscopy have also been used to characterize ensemble optical properties of DNA assemblies modified with metal nanoparticles. UV–visible spectroscopy has been used to measure DNA concentration-dependent properties93, whereas circular dichroism spectroscopy has typically been employed to identify the chiral signature of the final compound94.

In general, ensemble techniques are valuable tools to gather a global picture of the assembly process, where their focus is to quantify the fraction of the target structure obtained compared with the side products through the characterization of an average chemical–physical property of interest. Their major limitation is a lack of sufficient spatial–temporal detail. For such purpose, single-molecule techniques are instead preferable.

Single-molecule characterization

The main feature of a DNA origami structure is to provide a molecular surface where desired chemical species can be positioned at predictable nanometre distances. As each nucleobase of the DNA object can be chemically functionalized, this would in principle enable the positioning of two distinct molecules along two consecutive bases on the same helix, resulting in a spacing of only 0.34 nm along the helical axis. In practice, point modifications are separated by at least one and a half helical turns (ca. 5.4 nm) to allow easier identification with standard single-molecule techniques (although recent developments enable reaching sub-5-nm resolution). Both force and optical-based methods have been employed to characterize the structure and function of DNA origami objects95,96,97, such as atomic force microscopy (AFM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), cryo-EM, single-molecule fluorescence microscopy and, more recently, single-molecule force measurements.

The very beginning of the DNA origami era was associated with eye-catching AFM images that clearly demonstrated the success of the method and spurred on further research7 (Fig. 3e). By sensing the intermolecular forces occurring between the tip and the sample, AFM provides the height profile of the specimen deposited on an atomically flat surface — its detailed topographical map — with a lateral resolution of 1–2 nm. The capability of this technique to reveal fine structural features has recently been employed to better understand the folding pathway of planar DNA origami structures by providing accurate wide-field images of hierarchically self-assembled constructions11,81,98,99,100 (Fig. 3f). Modern AFM instruments also combine high spatial resolution with a temporal resolution of seconds to sub-seconds95, sufficient to monitor topological changes in single molecules101 (Fig. 3g) or DNA processing events in real time102,103. Although AFM is a powerful tool to characterize 1D and 2D structures, it may not be suitable for the imaging of 3D or multilayer DNA origami because the deformation caused by the AFM tip during scanning makes it difficult to obtain the complete topography of surface features in low-rigidity structures.

For the characterization of 3D DNA objects, TEM and cryo-EM are preferred instead. Uranyl formate or other uranyl salts are commonly used to produce negative stain contrast in TEM micrographs because they are excluded from the densely packed DNA structures. The result is a bright and fine-grained image of the specimen on a dark background. Image processing (for example, using EMAN2 software) can be used to assess the heterogeneity of DNA origami, identify structural flaws and reconstruct 3D models from TEM images of a single structure.

The first TEM images of 3D DNA origami structures showed the suitability of this technique to reveal the successful formation of the intended space-filled architectures17,18 (Fig. 3h). However, the high vacuum and dehydration conditions associated with TEM imaging may result in flattening and distortion of structures that display inner cavities. In such instances, electron microscopy imaging in fully hydrated cryogenic conditions is preferred, as it ensures structure preservation and enables observation of the macromolecule in the close to native state in solution. Using cryo-EM, the first pseudo-atomic model of a 3D DNA object was obtained with an overall resolution of 11.5 Å, confirming the formation of a structure with the expected topology104. Although the structural information gathered by raw individual electron microscopy images is relatively low, acquiring large sets of individual particle images and processing them semi-automatically using sophisticated post-imaging software tools results in a dramatic increase of the signal to noise ratio and, in most cases, leads to full reconstruction of the 3D structure with near-atomic resolution. TEM provides images of the specimen with a wide field of view and has successfully been used to characterize the formation of micrometre-large DNA origami hierarchical assemblies obtained by base stacking, guided hybridization or a combination of both20,82. Finally, although TEM has a lower time resolution, it can still be used to distinguish changes in structurally distinct states upon environmental changes in pH, salt concentration or temperature, and has revealed the triggered dynamics of molecular machines26.

Fluorescence-based techniques provide an indirect characterization of local molecular events occurring near dye molecules that are attached to the DNA surface using various bioconjugation methods. As the DNA objects are typically smaller than the diffraction limit of light (ca. 200 nm), their resolution by ordinary fluorescence imaging is limited. This has changed with the advent of single-molecule FRET and super-resolution microscopy. Whereas FRET relies on the distance-dependent energy transfer between a donor and an acceptor photoactive probe, the basic principle behind super-resolution imaging is the consecutive switching of fluorescent molecules between an 'on' and 'off' state. Stochastic reconstruction methods, such as point accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (PAINT)97,105, have been combined with the transient binding of short fluorescent DNA strands (DNA-PAINT) for the direct observation of dynamic events on DNA origami scaffolds106,107 (Fig. 3i). In general, single-molecule fluorescence techniques have been successfully implemented to describe local dynamic events and quantify distance-dependent molecular interactions, conformational dynamics and kinetics of diffusion processes108,109,110,111.

Finally, although still limited in its use, single-molecule force spectroscopy based on optical tweezers is a promising application. This technically challenging method has already been employed to observe the unzipping of small DNA origami domains99,112,113 and the kinetics of G-quadruplex unfolding within a DNA origami cavity114. Particularly when in combination with optical methods115, this method promises to be an essential tool for the investigation of dynamic events at the single-molecule level (Fig. 3j).

Applications

With proper chemical modification at specific locations, DNA origami structures provide a versatile engineering platform where nanoscale entities — from small-molecule dyes to massive protein complexes, inorganic nanowires and 3D liposomes — can be manipulated in a highly programmable manner. Prominent examples include nanomaterial fabrication that relies on precise control of molecular placement, as well as the study of biological processes resulting from well-organized molecular assemblies. In this section, we review selected DNA origami-based applications in materials science, physics, engineering and biology, with the hope that these developments of the past decade may offer a sneak peek into the technology's future impact.

Nanofabrication

Owing to their highly customizable geometric properties, such as size and shape, and their nanometre resolution, DNA origami structures have been used as templates or frameworks for the assembly or synthesis of diverse materials with nanometre precision. They have shown great promise in the nanofabrication of inorganic (metallic or non-metallic), polymeric and biomolecular assemblies and patterns, with enhanced structural stability and/or desired physicochemical properties6,27,74,116. Importantly, DNA origami-based approaches allow massive parallel fabrication (for example, 1012 copies of products in a single operation)6 either in solution or on a surface.

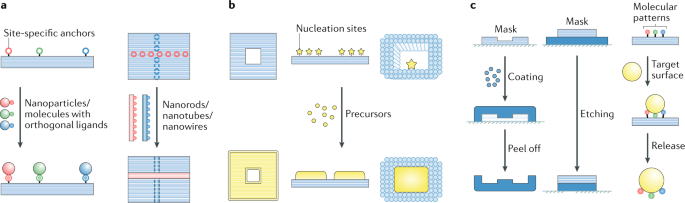

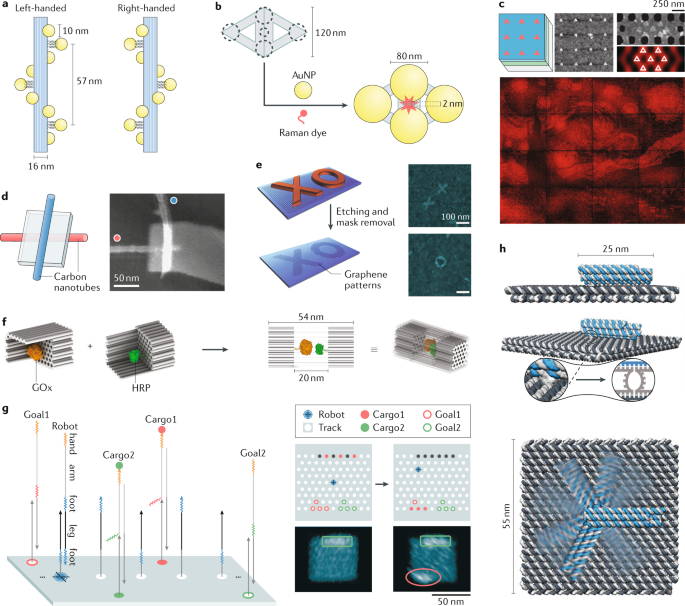

A representative nanofabrication approach (Fig. 4a) employs DNA origami templates with site-specific anchors (typically the staples or their appendices) to attach other prefabricated nanomaterials via user-defined specific interactions. This approach generates a highly programmable arrangement of atomic-scale discrete nanostructures such as nanoassemblies in solution (colloids) or on a surface (patterns), metal and semiconductor nanoparticle assemblies with prescribed heterogeneity, anisotropy and/or chirality117,118,119,120,121, and carbon nanotubes with defined alignments32,122,123. Further packing or assembly can then generate higher ordered 2D patterns124 or 3D superlattices125,126. In addition, the programmable reconfigurability of DNA origami allows nanoassemblies to be dynamically rearranged and creates tuneable physicochemical properties responsive to environmental stimuli31,120,127.

a | Site-specific assembly. The site-specific anchors on DNA origami templates enable spatial arrangement of nanoparticles/molecules or nanorods/nanotubes/nanowires with prescribed species, numbers and orientations32,118. b | In situ synthesis. DNA origami templates mediate the adsorption/reaction of certain precursors on their surface or in their cavities16,28,129. c | Nanolithography. DNA origami structures as masks or stamps enable the transfer of their shapes or molecular patterns to other materials33,135,137.

Full size image

During in-situ synthesis (Fig. 4b), precursors in solution (for example, metal ions, silicification precursors or lipid molecules) adsorb/react/deposit on DNA origami templates with or without prescribed nucleation sites128,129,130,131,132 and generate continuous architectures shaped by the morphologies of the templates or their cavities16,133. This approach promotes nanoarchitectures with almost arbitrary, user-defined geometries in solution or on a surface28,131,132,134.

DNA origami structures and their derivatives have also been employed as masks or stamps for nanolithography (Fig. 4c), enabling high-fidelity transfer of prescribed 2D nanoscale patterns onto other 2D or 3D materials33,135,136,137. In this way, the size and shape of 2D nanomaterials such as graphene can be precisely tailored for the fabrication of diverse electronic devices with nanometre resolution. In addition, the combination of traditional lithography and DNA origami-enabled site-specific assembly has facilitated large areas of spatially ordered arrays of functional nanoparticles and molecules on surfaces138,139,140.

Nanophotonics and nanoelectronics

Attractive optical and electronic properties arise from structural features with dimensions below the electromagnetic wavelengths (typically <100 nm). However, precise sculpting of materials at that scale is challenging. DNA origami-templated nanostructures with high structural programmability at the nanometre level allow tailorable optical or electronic properties, including tuneable conductivity, plasmon coupling, Fano resonances and plasmonic chirality, and hold great promise for applications in nanophotonics and nanoelectronics31,141.

Owing to localized surface plasmon resonance, the photonic properties of complex metal nanostructures composed of multiple nanoparticles are dependent on particle size, shape and the interparticle spacing and configuration. Rigid DNA origami templates enable precise arrangement of heterogeneous plasmonic nanoparticles, such as the coupling of large-size AuNP and AgNP (>40 nm)142, as well as small interparticle spaces (for example, sub-5 nm) with little variability143. This leads to prominent and predictable plasmon coupling and Fano resonances142 suitable for studying nanoplasmonic effects. A DNA origami-templated multi-particle plasmon coupling chain showed ultra-fast and low-dissipation energy transfer, exemplifying a new route to plasmonic waveguides144,145. In addition, DNA origami-based nanofabrication enables complex asymmetrical plasmonic nanoparticle assemblies44,118,120,146,147,148,149,150,151,152 with structural chirality and strong plasmon coupling. These properties interact differently with left and right circularly polarized light, leading to pronounced circular dichroism in the visible spectrum (Fig. 5a).

a | Left and right-handed AuNP nanohelices organized by DNA origami, which exhibit mirror symmetrical circular dichroism signals at visible wavelengths118. b | Raman dye molecules placed precisely in the gap among the AuNPs on DNA origami, presenting single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy142. c | Engineering photonic crystal cavity emission via precision placement of DNA origami139, enabling the creation of an image with 65,536 pixels (Vincent van Gogh's painting The Starry Night). d,e | Schematic and atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of vertically crossed carbon nanotubes (coloured red and blue) arranged by DNA origami32 (part d) and tailored graphene patterns resulted from nanolithography with metallized DNA origami structures as masks33 (part e), enabling field-effect transistor application. f | An enzyme couple, glucose oxidase (GOx) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP), encapsulated in the cavity of a DNA origami nanocage. Their spatial proximity in the confined environment enable enhanced cascaded catalytic activity109. g | A cargo-sorting robot on DNA origami that can transport cargos (Cargo1 and Cargo2, marked with red or green solid circles) to specified locations (Goal1 and Goal2, marked with red or green hollow circles) via toehold (coloured arrows)-mediated strand displacement reactions. The results visualized by AFM42 show cargo transfer from the initial locations (boxed) to the goal locations (circled). h | A DNA robotic arm driven by an electric field110. Upper to lower: side view, perspective view (with a close-up showing the flexible joint) and top view of the robotic arm (blue striped) that can rotate on the platform (grey striped). Part a adapted from ref.118, Springer Nature Limited. Part b modified from ref.142, Fang et al., Sci. Adv. 2019;5: eaau4506. © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed under a CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Part c adapted from ref.139, Springer Nature Limited. Part d adapted from ref.32, Springer Nature Limited. Part e adapted from ref.33, Springer Nature Limited. Part f adapted from ref.109, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Part g adapted with permission from ref.42, AAAS. Part h adapted with permission from ref.110, AAAS.

Full size image

By organizing multiple chromophores/fluorophores with distinct spectral properties, prescribed distances, orientations and/or donor to acceptor ratios, DNA origami platforms enable efficient light-harvesting antennas and photonic wires with long-range directional energy transfer35,36,153,154. Precise positioning of Raman chromophores or fluorophores between plasmonic nanoparticles can generate quantitative surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic142,155 or fluorescence spectroscopic responses156,157 (Fig. 5b), which provide promising materials for single-molecule sensing when coupled to target-specific ligands and trigger-responsive dynamic DNA self-assemblies. Precise placement of fluorophore-labelled DNA origami onto lithographically patterned photonic crystal cavities allows engineering of their coupling and thereby digitally controllable cavity emission intensity139 (Fig. 5c).

Finally, DNA origami allows shaping and arrangement of diverse materials with different conductive/semiconductive/dielectric properties and provides a new fabrication route for complex nanoelectronic modules and devices, such as nanowires with tuneable conductivity133, field-effect transistors based on spatially organized carbon nanotubes32,158 (Fig. 5d) or DNA-templated graphene nanoribbons33 (Fig. 5e).

Catalysis

Biocatalytic transformations are central to the production of metabolites, biomolecules and energy conversion in living systems. In very early DNA nanotechnology considerations, Seeman envisioned DNA structures with the potential to organize proteins in spatially well-defined patterns for structural analysis1. Today, we have realized that DNA nanostructures offer an excellent platform for spatially organizing enzymes owing to the unique addressability of DNA origami159.

The hypothesis motivating spatial organization of enzymes in reaction cascades is that the diffusion of small-molecule substrates between enzymes is proximity-dependent, and thereby the rate of the cascade is also proximity-dependent. The most common strategy for organizing enzymes (and proteins in general) in DNA nanostructures is to conjugate an oligonucleotide strand to each enzyme separately, by one of the many available methods for protein–DNA conjugation116. The DNA structure is designed with complementary single-stranded domains extending from the positions where the individual proteins in the cascade will be located, and subsequent addition of the DNA–protein conjugates attaches the conjugates to the DNA structure in the desired positions by hybridization160,161,162,163,164. The proximity hypothesis was challenged in a recent study, which argued that the negatively charged DNA structures to which the enzymes are anchored alter the local pH in favour of catalytic processes165. This argument cannot account for all of the proximity effects observed experimentally, however, and uncertainty about the proximity effect remains163,166.

In the studies above, the enzymes are confined in one or two dimensions. Another strategy is to confine enzymes in three dimensions to potentially enhance both the channelling of intermediates and the impact of the origami structure on the enzyme. In some examples, single proteins have been encapsulated in 3D origami structures90,167,168, whereas other cases have demonstrated encapsulation of enzyme couples (for example, glucose oxidase and horseradish peroxidase)109,169,170, forming enzyme cascades in DNA origami nanostructures such as a flat origami sheet169, an open-ended honeycomb-lattice DNA origami tube170 and a closed honeycomb lattice nanocage109 (Fig. 5f). In all three cases, both significant rate enhancement of the enzyme cascade and higher enzyme stability were observed171.

Computation

DNA is an information-carrying molecule with a high degree of thermodynamic and kinetic programmability because the rate of its toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions can be tuned25,37. Rational sequence design thus enables the formulation of both potential binding events in a DNA-based system and when and in what order these events must occur. Owing to these properties, DNA is a popular substrate for in vitro signalling networks and molecular computation, starting with Adleman's implementation of the travelling salesman problem172. Rational sequence design — often the last step in multiple layers of abstraction173 — finalizes the encoded algorithm and optimizes the emergent physical behaviour of DNA-based circuits. This principle of abstraction is also present in structural DNA nanotechnology. For instance, the CaDNAno design process is mostly sequence-independent, as it happens on a higher abstraction level. Compatible base sequences that allow the design to be physically implemented are generated only in the final step. The key distinction, however, is that, instead of structural blueprints, the base sequences in DNA computation encode algorithms — instructions on the propagation of cause and effect through binding events. This has resulted in the embedding of intricate programs into mixtures of DNA molecules, such as Winfree's square-root calculator174. However, the scaling and computation speed of these diffusive circuits is limited by their lack of spatial organization174.

DNA origami structures therefore provide a framework for scaffolding, co-localizing and compartmentalizing circuit components175. Spatial organization of DNA-based circuits through the use of origami frameworks can be exploited to accelerate reaction rates176, modulate stochiometry175, restrict or promote specific pathways177,178 and outputs179, compartmentalize distinct functional modules (for example, sensing, computation and actuation)180, decrease computation errors stemming from crosstalk and increase sequence recyclability176. Furthermore, owing to improved physiological stability over small ssDNA and dsDNA, structural DNA nanotechnology could open doors for in vivo computation, including the rewiring of cellular signalling pathways41,181.

Although localization mostly presents an optimization strategy for deterministic circuits, it enables entirely novel properties to emerge in systems that rely on stochastic methods. For instance, a DNA origami robot was designed that sorts unordered cargo into distinct piles, the algorithm of which relies entirely on a random walk and localized targets42 (Fig. 5g). Similarly, random walkers can be guided by their local landscape108. In another application, Chao et al. implemented a parallel depth-first search algorithm to solve mazes on DNA origami sheets based on randomly searching DNA navigators43. Other recent developments in DNA computing seek to use structural reconfiguration or even the assembly itself as a computational architecture100,182. Alternatively, the results from DNA-based combinatorial selection can be localized on DNA origami structures, thereby coupling unique structural patterns to specific input signals183. Such applications would not be possible without spatial organization.

Molecular machines

The structural stability of DNA origami relies mostly on Watson–Crick base pairing and base stacking, both of which are reversible non-covalent interactions. Such reversibility has been exploited as a conscious design choice; for instance, a nanocontainer that opens and closes has more applications than one that only encapsulates90,184. Among other strategies, simply leaving parts of the scaffold or staple strands as single strands readily introduces flexible and reactive domains into the origami structure, for example via toehold-mediated strand displacement. The challenging aspect is how to reliably navigate the resulting conformational state expansion. Over the past decade, there has been an influx of dynamic DNA origami devices that transition between two or more (semi-)stable states185. Dynamic DNA structures differ in the type of input trigger as well as in the number of accessible states, their actuation speed and whether transitions are reversible186. One approach, for example, is to use the intrinsic electric properties of DNA, such as the negative charges on the DNA backbone187, to fabricate an electrically controlled rotating arm that reversibly explores a continuum of states with only milliseconds of actuation time110,188,189 (Fig. 5h). Many of these devices combine the rigidity of dsDNA with flexible single-stranded domains in order to achieve a dynamic function. Alternatively, domains can be mechanically interlocked to sterically direct their motion190. A major goal for DNA nanotechnology is to create molecular machinery and motors that do not just switch between states upon sensing some external change but also are progressively fuelled through a closed state path and generate change externally191,192. This change can be in the form of potential energy (for example, by establishing new chemical bonds) or kinetic energy (for example, by rupturing chemical bonds or by translocation). In order to fabricate such machines, it will arguably be necessary to integrate multiple simpler devices, in the same way as different functional parts are combined to create macroscale machines185. This includes expanding the chemical scope beyond that of base pairing and stacking, for instance through the inclusion of proteins. A recent study combines RNase-based catalytic walkers with steric direction of a DNA nanostructure, where the resulting system converts potential energy from RNA-based fuel into the unidirectional microscale movement of an origami roller193. Notably, this motor moves autonomously and without the aid of any external gradient or patterning.

Drug delivery

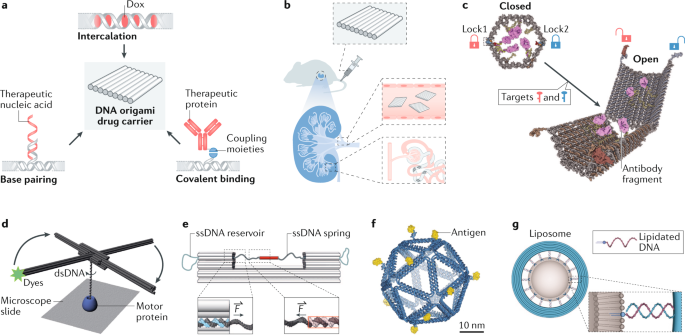

Exploiting DNA origami structures as carriers for drug delivery has garnered much interest39. First, as a natural biomaterial, DNA is biodegradable and shows little cytotoxicity194,195. Second, diverse therapeutic molecules and materials, including doxorubicin194,196,197, immunostimulatory nucleic acids198,199, small interfering RNAs200, antibodies184, enzymes40 and so on, can be readily loaded onto the carriers via various interactions such as intercalation, base pairing or covalent binding116 (Fig. 6a). DNA origami structures can also serve as containers with docking sites in their interior or within dedicated cavities, protecting the payloads from the environment and the environment from the payloads.

a | Representative drug loading strategies for DNA origami carriers, on the basis of DNA intercalation, such as intercalating for Dox delivery194,196,197, base pairing for delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids such as immunostimulatory nucleic acids198 and small interfering RNAs200, and covalent binding, such as HyNic/4FB coupling for antibody fragments184. b | Preferential renal uptake of DNA origami enables the treatment of acute kidney injury195. c | A logic-gated DNA nanorobot locked with two different aptamer motifs (red and blue locks) that can be opened in the presence of both target molecules (red and blue keys) on the cell surface and expose the antibody fragments (purple) inside184. d | A DNA origami rotor enabling tracking the rotation of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) relative to a genome-processing protein223. The dsDNA rotates when it is unwound by the protein bound on the substrate. The rotation can be amplified and tracked by the DNA origami rotor labelled with fluorescent dye (green star). e | A DNA origami force clamp240. Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) exits the clamp duplexes in a shear conformation (left inset; scaffold in dark grey and staple in blue) and spans the 43-nm gap. ssDNA reservoirs are located on each side of the clamp. The system of interest (here, a DNA duplex) is probed in shear conformation (right inset; scaffold in dark grey and complementary DNA in pink). f | An icosahedral DNA origami nanoparticle (blue) presenting 10 copies of an HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein antigen (yellow) in a spatially organized manner215. g | A DNA origami ring (blue) carrying multiple lipidated handles (pink curl with blue head) as a template allowing formation of lipid vesicles (grey) with controlled size253. F, force. Part b adapted from ref.195, Springer Nature Limited. Part c adapted with permission from ref.184, AAAS. Part d adapted from ref.223, Springer Nature Limited. Part e adapted with permission from ref.240, AAAS. Part f adapted from ref.215, Springer Nature Limited. Part g adapted from ref.253, Springer Nature Limited.

Full size image

One outstanding challenge for drug delivery is to efficiently cross biological barriers to reach the drug targets with minimal off-target effects201. Previous studies have shown that well-folded DNA nanostructures are more resistant to enzymatic degradation202 than ssDNAs/dsDNAs and are capable of entering live mammalian cells through energy-dependent endocytic pathways in an analogous way to some viral particles203,204,205,206. They can even cross cell walls in mature plants207,208. The dependency of cellular uptake on size and shape has also been investigated using DNA origami209,210. At the animal level, DNA origami structures are found to passively accumulate in solid tumours owing to enhanced permeability and the retention effect, enabling tumour-targeting drug delivery194. In addition, DNA nanostructures can penetrate mouse or human skin, suggesting applications in transdermal drug delivery to melanoma tumours211. Recently, DNA origami structures were found to preferentially accumulate in the kidney of a mouse, showing potential for treating kidney injuries195 (Fig. 6b). As these in vivo distribution tendencies are believed to correlate to the dimensions of materials212, the high structural customizability and monodispersity of DNA origami structures make it possible for them to selectively cross certain biological barriers; meanwhile, they can be retained elsewhere, enabling controllable distribution that is advantageous in these delivery studies.

To endow DNA nanostructures with active targeting ability, certain ligand molecules201,213,214 with known receptors expressed on target cells have been incorporated into DNA origami carriers. Owing to the addressability of DNA nanostructures, the species, numbers, density and orientation of these ligands can be precisely defined, allowing optimized cell targeting ability based on spatial pattern recognition by the cells201.

Physiological and intracellular environments are highly heterogeneous and therefore call for smart carriers capable of sensing environmental stimuli at different delivery stages and switching their structures/properties to adapt to them. For example, Douglas et al. developed a logic-gated nanorobot (Fig. 6c) with a DNA origami container locked by two different aptamer motifs184. Only when both aptamers bind to the corresponding cell surface receptors can the container be opened (for example, an AND logic that gives a positive output only when all inputs are positive), which allows conditional exposure of the drug molecules to certain cell types. A later demonstration successfully cascaded multiple nanorobots into logic circuits, such as a half adder, in living cockroaches, enabling delivery of antibodies towards their cells based on calculation results181. In another example, a DNA origami nanorobot was constructed that could be selectively unfolded by nucleolin enriched in tumour-associated blood vessels. This allowed local exposure of the encapsulated thrombins and promoted intravascular thrombosis, resulting in tumour necrosis and inhibition of tumour growth in mice40.

Compared with smaller DNA objects, such as tetrahedral DNA nanostructures that have also been intensively explored for drug delivery application201,203, DNA origami structures yield more complex shapes spanning a wider range of dimensions (typically 2 nm to hundreds of nanometres). This enables higher loading capacity and more complex patterning of the drug payloads. Given that many biological effects such as ligand-receptor recognition215 or cell internalization209,210 are known to be sensitive in this dimension range, DNA origami may gain more traction for this application than smaller DNA objects.

Some issues remain, however, such as the stability of DNA origami structures in a biological environment72 and possible immunogenicity of the exogenous nucleic acids216. Nevertheless, the potency of immunogenicity of these structures is highly dependent on the base sequence217, structural properties198 and chemical modifications29,218. Thus, by rationally engineering those parameters, the risk of immunotoxicity could be minimized6,29,216,217,218. By contrast, DNA structures with high immunogenicity can be used as adjuvants for vaccines in applications such as cancer immunotherapy198,199.

Bioimaging and biophysics

DNA origami structures serve as standards, markers or structural support for molecules of interest in biophysical studies, allowing for the control and measurement of molecular stoichiometry, dimensions and collective behaviour. Placing a designated number of fluorophores at predefined positions on DNA origami structures (often sheets and rods) generates calibration standards or references for fluorescence microscopy to identify, count and measure the spacing between molecular species, for example fluorescently labelled protein constituents within a complex34,106,219,220,221,222 (Fig. 3i). In some cases, a DNA origami structure helps to monitor biologically relevant movements just by virtue of their rigid body and well-defined shapes. For example, a DNA origami rotor was built with its centre attached to a dsDNA segment to track dsDNA rotations induced by the genome-processing enzymes RecBCD and RNA polymerase223 (Fig. 6d). Similarly, stiff DNA rods enhance the signal to noise ratio of an optical trap224,225 or FRET-based force measurement226, leading to high-resolution study of weak biological forces (in the order of a few piconewtons) such as base stacking225 and cell-substrate traction226. Labelling DNA filaments with motor proteins and fluorophores enables measurement of the velocity, processivity and stall force of myosin115,227,228, dynein and kinesin229, both individually and in motor ensembles.

In addition to optical imaging, DNA origami structures have been used to aid AFM and electron microscopy studies. 2D DNA origami sheets and frames are common substrates for AFM visualization of molecular motions230 (Fig. 3g), including DNA structural transformations such as the B–Z transition231 or the G-quadruplex formation101, DNA–enzyme interactions such as transcription232, recombination233 and methylation234, and movements of artificial DNA motors108,177,235. Clam-shaped DNA origami structures have facilitated the electron microscopy analyses of nucleosome interaction and stability, using their open or closed conformations to signify various states of nucleosome assembly236,237,238,239. A DNA origami 'force clamp' was built, where a U-shaped body suspends a segment of DNA under a defined tension of 0–12 pN (Fig. 6e) and enables single-molecule force spectroscopy studies of tension-dependent Holliday junction isomerization240, DNA nuclease activities241 and formation of the transcription pre-initiation complex242. Barrel or clamp-shaped 3D DNA origami structures have found applications in the cryo-EM structural determination of proteins, where DNA nanostructures serve to define the thickness of a vitrified ice sheet243, create a hydrophobic environment to stabilize membrane proteins244 and orient DNA-binding proteins at desired rotation angles245.

DNA origami creates an artificial microenvironment to study the molecular mechanisms of biological processes. An illustrative example is the study of multivalent antigen–antibody and protein–aptamer bindings on a DNA origami platform, where antigens and aptamers are organized in assorted arrangements to identify the molecular patterns that contribute to avidity215,246,247,248 (Fig. 6f). Crowding dsDNA with protospacer-adjacent motifs has led to enhanced Cas9/single guide RNA binding and more efficient dsDNA cleavage249. Varying the nucleoporin type and grafting density inside a DNA origami cylinder has been shown to significantly impact the collective morphology and conductance of the intrinsically disordered proteins250,251. Using DNA origami-templated liposome formation techniques (Fig. 6g), liposomes and membrane proteins have also been placed at defined distances and densities to study the biophysics of membrane dynamics252,253,254,255. Flat or curved DNA origami surfaces outfitted with amphipathic molecules such as cholesterol and peptides can lead to membrane binding and deformation and are useful for studying membrane mechanics256,257,258,259,260. Finally, DNA origami structures bridge the gap between top-down lithography-based devices, such as solid-state nanopores, and bottom-up molecular engineering, such as chemical synthesis and macromolecule self-assembly. They can therefore create advanced analytical tools, for example signal-enhanced long-distance FRET pairs261 or nanopores for measuring molecular recognition262,263, for biophysical experiments.

Reproducibility and data deposition

The general standards of DNA origami assembly have been continuously developed, ranging from DNA origami designs to purification methods to reconstruction models for TEM imaging, among others73,264. To ensure high reproducibility, several important aspects should be carefully examined.

First, although a one-pot reaction can be used for the self-assembly of DNA origami, this often results in many by-products such as dimers, trimers and other aggregates. Various assembly conditions, such as the annealing procedure and the cationic strength, can significantly influence the yields of the target products and by-products. Optimization of the annealing procedure, especially the annealing temperature intervals, is crucial to achieving the target object with high yield. Furthermore, cationic strength is another critical parameter for optimization in order to avoid DNA origami dissociation through electrostatic repulsion. The TAE buffer with Mg2+ (5–20 mM) is typically adopted in most protocols for DNA origami assembly.

Second, purification of the DNA origami is of great importance. There are five typical purification methods: PEG precipitation, gel purification, filter purification, ultracentrifugation and size-exclusion chromatography. The most appropriate purification method for a particular experiment should be selected based on the yield and duration as well as the volume limitation, dilution, residuals and damage46,73 For example, PEG precipitation can be adapted to enhance the recovery yield of target species after purification, but it also introduces residual PEG molecules. Filter purification with molecular weight cut-off membranes provides residual-free separation. Although it has volume limitations, this is an effective method to quickly separate DNA origami from excess strands (≈30 min) and to adjust buffer conditions. Gel purification is suitable for bandpass molecular weight separation, such as complex DNA origami structures and nanoparticles. Size-exclusion chromatography is suitable for bandpass molecular weight separation without introducing residual compounds and is commonly employed in protein biochemistry.

Last, the storage temperature and the cationic strength are both crucial for DNA origami stabilization. In general, DNA origami is thermally stable at temperatures ≤55 °C in solution. However, it can also be stable at temperatures >85 °C with photo-cross-linking-assisted thermal stability80. DNA origami can also be lyophilized and stored under freezing conditions265. For the cationic strength, many approaches have been reported to protect DNA origami from destabilization, especially at low Mg2+ concentrations or without Mg2+ (refs70,71). In addition, block copolymers could be a reversible protection and potential long-term storage strategy for DNA origami nanostructures as they can protect nanostructures from low-salt denaturation and nuclease degradation30,266.

To ensure data reproducibility, researchers must provide sufficient general information as well as detailed experimental conditions and procedures in their publications. For instance, general information including DNA origami design, assembly and purification procedures, quality analysis approaches, AFM and TEM sample preparations and data pre-processing should be provided. For hybrid DNA origami structures, modifications of the attached nanoparticles or proteins, their conjugations on the DNA origami and the purification procedures of such DNA origami complexes should be carefully described. For drug delivery using DNA origami, it is often difficult to unify the minimum reporting standards owing to the complexity of biological experiments. Typically, this method can follow the general rules required by biological journals. In addition, the experimental protocols and methods, assembly materials and sources, design and analysis software should also be carefully listed and described in detail. Free software, such as CaDNAno and EMAN2, may be deposited in an open source repository. Finally, data deposition in public repositories is highly recommended. For example, scaffold sequences can be deposited in GenBank.

Limitations and optimizations

The remarkable breadth of applications not only highlights the power of DNA origami but also reveals roadblocks that need to be removed in order for the technology to reach its full potential. Somewhat surprisingly, the first limitation is the structural design of DNA origami, which, to date, remains a hurdle for those new to DNA nanotechnology and is sometimes challenging even for users familiar with the technique. Although many design and simulation tools8,9,10,15,47,48,49,50,56,59,61,62,63,73,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274 have been developed and made available to the public, the more versatile design tools generally require a considerable amount of user input and technical know-how. In addition, the better automated tools are typically geared towards specific types of construct, such as 2D meshes with a triangulated framework48 or wireframe polyhedrons9,15,47. Ideally, we would enjoy a suite of software that streamline the design and simulation process, serving both as a tool to easily convert simple geometrical models into DNA origami designs and as a sandbox for users to explore new design concepts. The field has made steady strides towards this goal by interfacing multiple design-simulation software, developing more user-friendly interfaces and allowing for post-simulation touch-up to optimize design iteratively.

Second, the functionalization of DNA nanostructures in most cases necessitates chemically modifying DNA with molecules of interest. Even with a multitude of well-documented DNA-modification chemistries and a continuous stream of emerging bioconjugation methods, finding a robust and controllable conjugation method for a specific application can be a daunting task. A few review articles116,275,276 summarize the field's progress in this area. Although the most appropriate conjugation method depends on the application, good candidates are generally easy to perform in that they require few steps and use commonly available chemicals, generate stable products with decent yield, allow stoichiometric control and retain the structure and function of the DNA-modifying moieties. Of equal importance to selecting a suitable conjugation chemistry are careful optimization and rigorous quality control when placing guest molecules on DNA origami structures. These include purifying functionalized DNA structures84, quantifying the labelling efficiency and examining/eradicating any undesired behaviours, such as aggregation or loss of fluorescence, as a result of DNA attachment.

Third, a clear picture of the DNA origami assembly mechanism remains elusive. Although we are equipped with advanced techniques to design and produce desired DNA origami shapes, we need to better understand how hundreds of DNA strands self-assemble to form such complex structures. Besides driving a higher assembly yield of the target structures, the ability to clearly define DNA origami folding pathways will enable rationally designed dynamic assemblies that can toggle between a few metastable conformations with low energy barriers between them, which is a feature found in many protein machineries. Numerous high-quality studies have shed light on this long-standing question, including systematically testing DNA origami design variants that lead to different folding outcomes11,69,277, measuring the global thermal transition during DNA origami assembly and disassembly76, directly observing assembly intermediates98 and monitoring the incorporation of selected staple strands12,92. Many of these studies suggest a multistage, cooperative folding behaviour. Future efforts to depict such complex mechanisms will benefit from high-throughput analytical methods278 and simulation frameworks50,56,59,61,62,63,73,270,271 for DNA self-assembly.

Fourth, the size of a DNA origami structure is limited by the length of its scaffold strand, typically 7–8 kb long. To obtain larger structures, one has to use a longer scaffold65,67 and/or stitch multiple DNA origami structures together20,21,26,279. Both methods have been successful thanks to bacteriophage genome engineering and hierarchical DNA self-assembly81,280,281,282 via sticky-end cohesion or blunt-end base stacking. These successes, however, often come at the expense of a marginal to severe drop in assembly yield. Although the field has largely relied on the M13 phage genome as scaffold strands for DNA origami production, ssDNAs that are multi-kilobases long with fully customizable sequences are now available68,217. Thus, in principle, a geometrically complex, fully addressable DNA origami structure can be synthesized from multiple scaffolds of orthogonal sequences in one pot, circumventing certain problems associated with exceedingly long ssDNA, such as instability or kinetic traps, and hierarchical self-assembly, such as slowness and reduced efficiency. A related practical issue is how to generate staple strands in a cost-effective way to fold these massive structures (that can reach the gigadalton scale) in large quantities. The most promising solutions today are enzyme-mediated in vitro amplification of synthetic DNA oligonucleotides283,284 and biological production of DNA strands in bacteriophages283,285. Using the latter approach, several hundred milligrams of DNA origami structures were produced at a fraction of the cost of using conventional synthetic DNA285.

Last, certain intrinsic properties of DNA, such as its negative charge and susceptibility to enzyme degradation, may limit its applications, especially in a biological environment (for example, to deliver drugs to the bloodstream or the intracellular space)29. On the other hand, certain applications in physics and materials science, such as high-temperature etching or 3D lithography, can test the thermal and mechanical stability of DNA origami structures. In this case, the physical performance of DNA origami can be enhanced with a combination of DNA modification chemistries such as photo-cross-linking DNA nucleotides80,286,287, wrapping exposed DNA surfaces with lipid bilayers29, shielding DNA backbones with polycationic polymers30,218,266,288,289,290 and coating DNA with silica28. By chemically or physically separating DNA from the environment and strengthening the links between DNA strands, these modifications help DNA origami structures survive low-salt, high-heat conditions, resist nuclease digestion, evade immune surveillance, prolong in vivo circulation and avoid surface deformation.

Outlook

The future of the DNA origami technique, and structural DNA nanotechnology more generally, will be shaped by ambitious technology developers constantly pushing technological frontiers and a diverse group of users, who will introduce new inspirations and challenges to fuel future innovations. Interesting scientific questions that will have to be addressed involve improvement of the chemical versatility of the structures, further improving speed and robustness of folding, and the realization of isothermal and in vivo assembly of nucleic acid nanostructures. Improved chemical versatility will enable novel applications in materials science, catalysis, nanomedicine and molecular robotics, whereas isothermal and in vivo assembly will be important for biomedical applications and synthetic biology.

Molecular programming and automation

DNA origami is a robust, sequence-programmable, nanometre-precise self-assembly technique, which is amenable to automation. It is not incidental that researchers in DNA nanotechnology and computing have dubbed their approach molecular programming. Quite literally, DNA origami structures can be programmed using computer-aided tools8,15 without much knowledge about their chemical details. Arguably, the development of the caDNAno design program was one of the major catalysts for the field8, allowing even newcomers to design complicated supramolecular structures with a good chance of success. Since then, a series of other design software packages have been developed for different types of origami structure (Table 1).

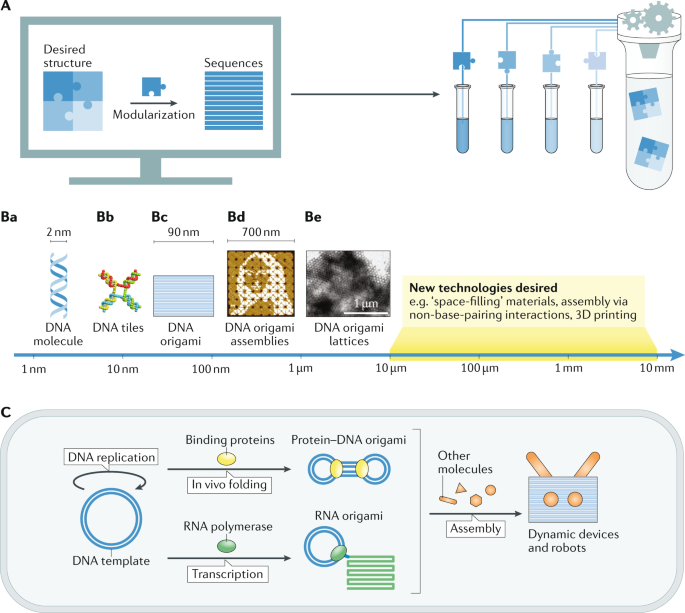

It is therefore expected that one line of research will continue to be devoted to the molecular programming of nanostructures. This will involve an even stronger interconnection between computational design, automated synthesis and assembly of the structures. This could ultimately lead to a completely automated process for the generation of DNA-based nanostructures potentially combined with on-demand DNA synthesis291 (Fig. 7A). Design rules are expected to further improve based on a better biophysical understanding of the origami folding process.

A | Modular, computer-aided design and automated fabrication. We expect that the integration of these techniques could lead to a completely automated process for the generation of on-demand nanostructures, without the need for much knowledge about their chemical details. B | Multiscale manufacturing will require the integration of different, scale-dependent assembly strategies into a consistent workflow — ranging from the formation of DNA helices (part a) over DNA tiles74 (part b) to origami structures7 (part c) and larger assemblies, such as DNA origami arrays21 (part d) and 3D crystals82 (part e). Even larger length scales may be accessed by interfacing origami with other (non-DNA) manufacturing technologies21,74,82. C | In vivo production of DNA/RNA origami and further assembly of dynamic devices and robots. DNA templates (blue) may be replicated in vivo and folded with intracellular DNA-binding proteins (yellow), forming protein–DNA origami structures303; or they can be transcribed into RNA origami structures when transcribed by RNA polymerase (green)23,299,304. These nucleic acid structures can be further integrated with other intracellular components (orange) to form dynamic devices and robots in vivo. Part Bb adapted with permission from ref.74, ACS. Part Bc adapted from ref.7, Springer Nature Limited. Part Bd adapted from ref.21, Springer Nature Limited. Part Be adapted with permission from ref.82, Wiley.

Full size image

Chemistry for applications

DNA origami has become popular because it meets the need for a molecular technology that enables the positioning of molecules and nanoparticles with nanometre precision and with a defined stoichiometry, potentially addressing a wide range of problems in nanoscience and in the life sciences.

As the origami field moves more towards applications, most researchers will deal less with the refinement of the technique itself than with coping with the specifics of their application. Much future research will therefore be devoted to resolving chemical requirements specific to certain applications, such as making DNA origami chemically and physically stable, and developing molecular adaptors for functional components116. Chemical stability will involve modified DNA and the careful design of sequence and structure to avoid undesired binding and degradation or disruption by enzymes. Physical stability — by which we mean both thermal and mechanical — can be enhanced by cross-linking or addition of stabilizing ions and surfactants. In addition, a better mechanistic understanding of the origami assembly/disassembly process will also clarify which types of origami design provide the highest physical stability.

Dynamic devices and robots